The art exhibition, “Mining the HMNS: An Investigation by The Natural History Museum,” in Houston, Texas, raises the question: “Is the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences a museum, or a PR front for the fossil fuel industry?”

The exhibition is a collaboration between The Natural History Museum, a mobile museum created by Not An Alternative, a Brooklyn based collective engaged in art and activism, and t.e.j.a.s. (Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services), a community-based activist organization in East Houston.

It is part of the group show, “Shattering the Concrete: Artists, Activists and Instigators,” at Project Row Houses, an arts organization that explores “art’s role in challenging the current political paradigm and fomenting political change,” on display through June 19.

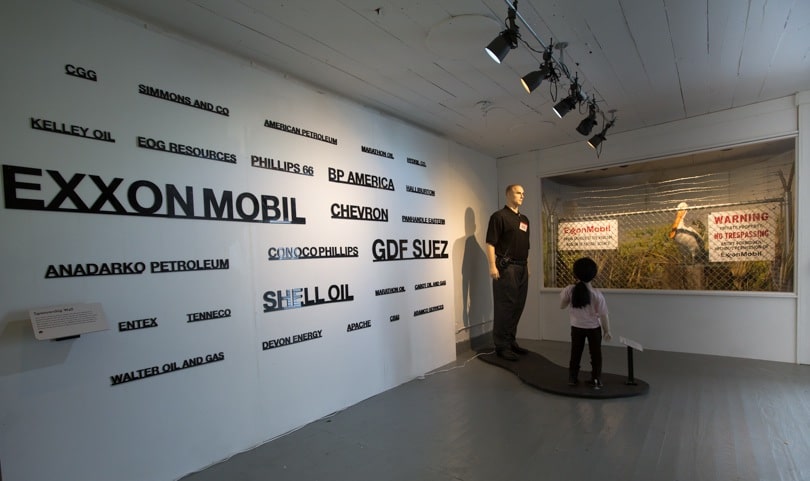

The Natural History Museum’s exhibition parodies elements featured in the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences (HMNS), the Wiess Energy Hall. In the show is a recreation of a wall crediting donors inside the HMNS.. While a wall in the HMNS displays the donors’ names scaled according to the size of donations (the larger donors are spelled out with larger letters), the Natural History Museum’s wall lists the names of HMNS’s donors with letters sized to the donors’ greenhouse gas emissions.

“You won’t find much about global warming or benzene pollution in the Wiess Energy Hall,” a Houston Chronicle editorial stated, pointing out: “There’s an academic truth in this criticism of fossil-fueled donations.”

“Since its inception, the Wiess Energy Hall has been dedicated to the science of energy and forthright about its sponsorship.” Latha Thomas, a representative for the HMNS wrote DeSmog in an email. “HMNS is dedicated to presenting an objective, forward-looking perspective on the current energy mix—and how sustainable technologies and responsible usage might improve the world of tomorrow. We take this responsibility seriously for all of our exhibition and education programs, regardless of how our exhibitions are funded.”

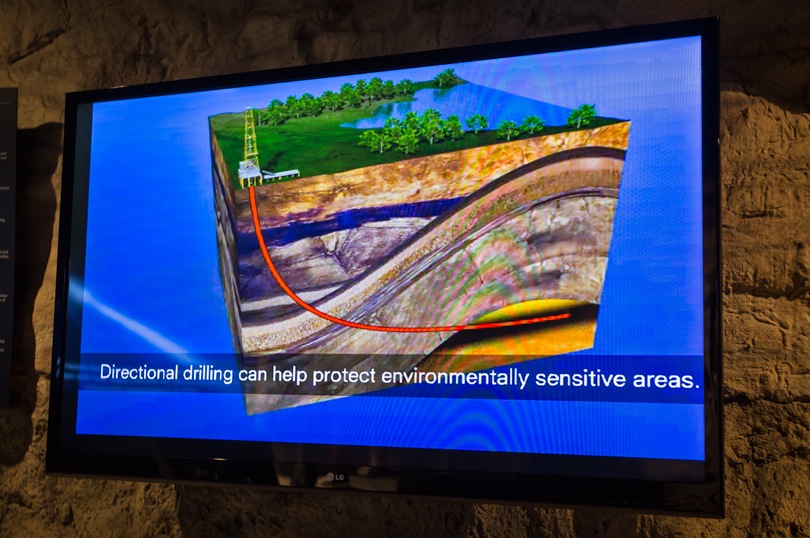

Video display in the Wiess Energy Hall ©2016 Julie Dermansky

“Mining the HMNS” features a model of a dinosaur equipped with an air-monitoring device. A map indicates sites where t.e.j.a.s. plans to place such dinosaurs to test the air quality in communities that share a fenceline with industrial facilities in East Houston, including Manchester, a predominantly Hispanic working-class neighborhood.

Dinosaurs that will be used in air tests. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Diagram showing where dinosaurs will be placed for air tests ©2016 Julie Dermansky

The air quality tests will be done in some of the same neighborhoods located next to industrial sites that the Houston Chronicle tested in 2005. The Chronicle found Manchester’s air laden with toxic chemicals and dangerous to breathe.

The Natural History Museum plans to give the local community new data on the air quality that it needs to hold regulators and industry accountable.

Group on a “toxic tour” led by t.e.j.a.s. in Hartman Park across from Valero Houston Refinery. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

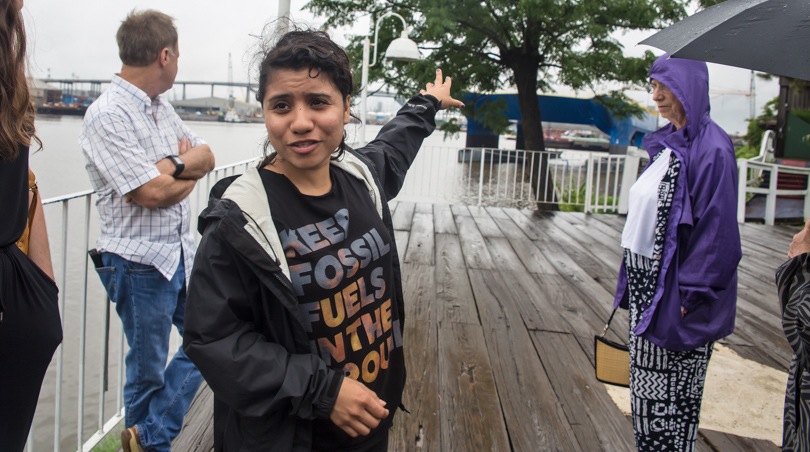

In conjunction with the exhibition, t.e.j.a.s. led “toxic tours” from the Project Row Houses to nearby recycling plants, a Superfund site, Houston’s ship channel, and Hartman Community Park in Manchester, across from Valero Houston Refinery.

On June 4, during the last tour given with the project, a siren at the Valero Houston Refinery went off as the tour group entered Hartman Park. Yudith Nieto, a representative of t.e.j.a.s. who grew up in Manchester, explained that warning sirens going off in that area are a common occurrence, but stressful all the same. The workers in the plant know what happened to cause the siren to go off but no one in the community is told what is going on.

In case of an accident, the usual solution offered by officials is to direct residents to shelter in place, a solution Nieto doesn’t think is ideal because inhaling chemicals following an industrial accident can cause lasting health problems.

Yudith Nieto talking to a group during a “toxic tour” at Houston’s Ship Channel. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Yvette Arellano with Jane Collins during a “toxic tour” at Buffalo Bayou across from Sims Metal Management’s Proler Southwest recycling facility. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Yvette Arellano, a t.e.j.a.s. research fellow, informed the tour group that children in low-income African-American and Latino neighborhoods like Manchester suffer from high rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases caused by the diesel exhaust from trucks, trains, and ships.

During the tour, t.e.j.a.s. explained the impacts on communities in the vicinity of energy production facilities that are not addressed in HMNS’s Wiess Energy Hall.

Wiess Energy Hall is not the only natural history museum display that fails to connect the fossil fuel industry to climate change. Other popular science museums in Texas, including the Perot Museum or Nature and Science in Dallas and the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History, have similar industry-sponsored energy halls.

Visitors at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science. ©2014 Julie Dermansky

Model of a Chesapeake drill rig in the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History in Texas. ©2013 Julie Dermansky

“Museums like the HMNS are tax-exempt, non-profit entities – as such, they should prioritize the public good over private interests,” Beka Economopoulos, founding director of The Natural History Museum project, told DeSmog.

Since its inception in 2014, The Natural History Museum has offered mobile exhibitions along with public programming that highlight socio-political forces that shape how natural history is presented in various museums.

“The American Alliance of Museums ‘Code of Ethics’ states that it’s incumbent upon museums to preserve the rich and diverse world we have inherited for posterity. Acting not only legally, but also ethicall,.” Economopoulos said. “We’d argue that on both counts the HMNS fails.”

Video: Drilling game at the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences

“The museum of the future should be a genuinely multidisciplinary space,” author and social activist Naomi Klein, who is on the museum’s board, wrote in a statement about The Natural History Museum project.

Klein said:

“If we’re talking about climate change, it wouldn’t just be talking about climate change as a problem of too much carbon in the atmosphere. It would be telling us why it’s there and who the interests are behind it, and what the real structural barriers are to progress.”

In 2015, The Natural History Museum wrote a letter signed by dozens of climate scientists and environmental groups that went to 330 institutions urging them to cut ties with the industry responsible for climate misinformation.

“When some of the biggest contributors to climate change and funders of misinformation on climate science sponsor exhibitions in museums of science and natural history, they undermine public confidence in the validity of the institutions responsible for transmitting scientific knowledge,” the letter states.

The letter was part of a campaign urging science museums to cut ties with the Koch brothers. David Koch, who was on the board of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and the American Museum of Natural History in New York, has donated millions to both institutions.

The letter states: “Mr. Koch also funds a large network of climate-change-denying organizations, spending over $67 million since 1997 to fund groups denying climate change science.”

Less than a year after the Natural History Museum’s letter, The New York Times reported that David Koch left his position on the board of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. A museum spokeswoman told the Times, “that his departure was not related to the criticism but simply because his term was ending.”

Energy companies’ contributions to European natural history museums also threaten curatorial freedom. Internal documents from the Science Museum in London, obtained by the Guardian, show Shell tried to influence the presentation of a climate change program it sponsored. Though the museum claimed no changes were made due to the sponsorship, Chris Garrard, from the anti-oil-sponsorship campaign group BP or not BP?, told the Guardian that the emails “reveal that the Science Museum is a significant cog in Shell’s propaganda machine.”

According to t.e.j.a.s.’ Bryan Parras, the bias in the Wiess Energy Hall is almost laughable. He knows only too well what is being left out, and finds it troubling that some of the docents at the HMNS giving tours of the Wiess Energy Hall work for the very companies that underwrote the exhibition.

“Employees of exhibit sponsors who give $25,000 or more to the museum get priority training and scheduling as docents,” Economopoulos told DeSmog. “Oil and gas companies have notoriously funded and spread climate science disinformation, confusing the public, and lobbied to block industry regulation.

The HMNS‘s Wiess Energy Hall trains visitors to take a perspective on energy that is the same as its corporate sponsors. The analogy that comes to mind is that it is the equivalent of an army recruitment center at Disneyland. The exhibit functions as propaganda and recruitment – indoctrinating people into the ideology of the industry.”

Economopoulos is also critical of a Texas coastal ecology exhibit in the HMNS. It represents the local coastal ecology, but excludes any indication of industry’s impact on the landscape. It leaves out elements t.e.j.a.s. points to on its toxic tours, like ‘No Trespassing” signs and warnings not to eat the fish.

“It’s as if the museum exhibits are organized around hiding the negative effects of the fossil fuel industry. Where the museum leaves off, t.e.j.a.s. picks up,” Economopoulos said.

For years, t.e.j.a.s. has led toxic tours for those wanting to learn about what is going on in East Houston neighborhoods. Arellano told DeSmog that she hopes the tours they gave in collaboration with The Natural History Museum inspire a new audience to help fight for social and environmental justice.

Yvette Arellano with Gayle Waden at Mining the HMNS exhibition. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Manchester resident in front of her home located across from Hartman Park. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Gayle Waden, a Houston resident and arts administrator for Project Row Houses who was on the toxic tour, told DeSmog that while she is familiar with the ill effects of the oil and gas industry, she didn’t realize how close the Manchester community was to the industrial sites. One house sandwiched between storage tanks across from Hartman Park is an image she won’t forget.

View from 610 that leads into Manchester. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Blog image credit: “Mining the HMNS” at Project Row Houses. ©2016 Julie Dermansky

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts